Migrations across time

A connection from past to present, from my story to your story to their story.

I recently moved to Brooklyn. People are everywhere. Two young men push a shopping cart full of empty bottles down the sidewalk. Children saunter towards the park, weaving between and around the adults that accompany them. Millennials in long coats and tiny sunglasses walk with coffees in hand, airpods in ear. An old woman scratches a lottery ticket outside the bodega. A young couple kiss on the corner, a bouquet of flowers peeks out of the bag on her shoulder.

Life is happening here.

I pass an older Black man as I walk down Myrtle Avenue. His dark, smooth skin is especially beautiful in the morning sun. He has an angular face, dark brown eyes. His wide shoulders hunch inside his sweatshirt and jacket. He feels tense, or maybe I am.

A latino man with a half empty box of candy walks in between us, crossing a few feet in front of him.

“You migrants make niggas want to kill you. Get the fuck off Myrtle Avenue.” He yells with bass in his voice, his chest pumped. “Get the fuck off Myrtle Avenue” he repeats as the man continues walking.

I look behind my shoulder. I slow down. I look back again and contemplate if I should go say something and what that would be? I keep walking. I turn again. A white man, young, tall approaches the Black man. They talk in a way that seems familiar. Their faces close together. The yelling subsides a bit, eventually I don’t hear anything. I put my airpods back in and continue down the street.

I pass a little brown girl with bangs almost covering her eyes and two long pigtails. We smile at each other. She tugs the leg of her father (maybe) who I only then notice. I don’t slow down enough to read his sign but catch the words “Venezuela” “migrant” “please.” I have no offering besides a toothless smile and nod. I think about buying them some water and a few pastries from the bakery I’m trying to find. I don’t find the bakery. I don’t take the same route home.

We are conditioned to believe there is not enough for all. That places, streets, blocks, homes are meant to be owned by someone or by some people. That when we say this place is “ours” it means not for you. Scarcity is a myth we have bought into and a powerful way to sow discord among the very communities who could, together, create an alternative society.

How do we contextualize migrations of people across time and place? How do we disrupt patterns of divisiveness that plague our society? Without finding a different way through, we will continue to be beholden to systems that create more harm than opportunity for the majority of people, and ultimately for all of us.

The Great Migration

My own great grandmother, Viola Benzina Owens (née Murray), and great grandfather, Frank Owens, on my father’s mother’s side were born in South Carolina in the 1890s. They met in Charleston, got married, had two children and then moved to New York sometime in the late 1910s. Their life and movement from South to North coincided with what historians and everyday Black folks call “The Great Migration.”

Isabel Wilkerson, Pulitzer-Prize winning author describes the Great Migration of 6 million Black Americans from the Jim Crow South to the northern, midwestern, and western United States from roughly the 1910s until the 1970s as a time when Black people were “seeking political asylum in the borders of one’s own country.”1

The reasons we fled? To escape racial violence, poverty, segregation, exploitation, unlivable conditions. Conditions created and sustained by the state of America that proclaimed to provide the right to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” nearly one hundred years before abolishing the institution of slavery. This same America is the country whose biggest export is unfettered capitalism and weapons of mass destruction, which have created and continue to create conditions of violence, poverty, segregation, exploitation, and unlivable conditions in so many parts of the world.

When we tell the story of our nation, we tend to fast forward often. The Great Migration is no exception. We jump from lynchings in the South to Black people living in brownstones in Harlem and building thriving communities in Chicago. We skip the reality of Black migrants from the American South being unwelcome, ostracized, and sequestered into poor, overcrowded communities.

“Unskilled and undereducated black workers were spit out by the system like so many undigestible watermelon seeds.” –[In reference to the Great Migration] Maya Angelou, Letter to My Daughter

Take the “red summer” of 1919 as an example. After World War I, an economic recession fueled backlash against Black Americans, including in northern cities where job competition had become more intense due in part to the Great Migration. In that year alone, hundreds of Black people were killed during incidents of racial violence and more than 1,000 were left homeless as white riots destroyed communities. At the same time, we see an uptick in activity of and enrollment in the Ku Klux Klan.

There are countless stories we are often not taught (and increasingly in danger of never being discussed in schools) about racial intimidation and violence in our country. A story I recently learned about takes place in Maine in 1919:

Samuel and Roger Courtney were brothers from a prominent Black family in Boston who became two of the dozen or so Black students enrolled at the University of Maine. On a cold April night, perhaps there was even still snow on the ground, a mob of 60 white classmates of theirs, stormed their dorm room, forced horse halters around their necks, walked them four miles to a central part of campus, forced them to strip naked in the cold, dead of night, held them down and shaved their heads, had them cover each other in hot molasses, dumped a bucket of feathers (which they emptied from their dorm room pillows) upon their cold, sticky skin, and gathered hundreds more of their peers to the livestock pavilion to watch.

Local police arrived at the scene hours after being alerted. No one was arrested. There was no official condemnation from the University of Maine (until 2020). Rather, Robert J. Aley, the President at the time, released a brief statement that claimed “The race questions was not the cause of a recent hazing episode…” Rather, the freshmen who perpetuated were “resenting of the treatment they received” from Roger and Samuel, and that something like this was “likely to happen at any time, at any college, the gravity depending much upon the susceptibilities of the victim and the notoriety given it.” In other words, it was the brothers’ fault.2

Samuel and Roger never finished their studies. Both died within a decade or so from this tragedy. I only learnt of this story from the diligence of one former faculty member, Karen Seiber, who was inspired to look into the institution’s racial history after the protests in 2020.3

Thanks to her and the protestors who inspired her action, Samuel and Roger, are now knowable. How many aren’t?4

Across this country, from Mississippi to Maine, Black folks were unwelcome. Some who had the means were able to make the sojourn north. We knew complete freedom from oppression and from violence was not in the cards — yet, like my own ancestors, Viola and Frank, we went anyway. In search of something, with a little hope in our pocket.

If there was a wall on the Mason Dixon line, I think most Black people would’ve kept going. Would have gotten over that wall like their lives and the possibility of their children living, depended on it.

A Different Story

The echoes of history sometimes seem so obvious, but we fail to pause, connect, and try something new.

The Black-White paradigm in this country is the foundational model of oppression for anyone who has been othered at some point. What they said about the Irish, they learned from what they said and did to Black people. What they said about the Chinese, they learned from what they said and did to the Irish. Then the Irish and the Chinese became American and some of them did and said what was done to them to Black people. And now some Black people are saying and doing things to recently arrived migrants.

They’re taking our jobs. They’re having too many children. They’re dirty. They’re not like us. They’re dangerous. They are taking something that is OURS. They don’t belong in this school, neighborhood, country.

But, there have been and are people willing to tell a different story. They (we) are eager to create a new sense of belonging.

Blair Mountain

Around the same time as white violence erupted in the north as a result of the great migration, class solidarity across racial lines also had its moments of glory.

In the 1900s in southern West Virginia, white families, Black families, often en route from fleeing the deep south, immigrant families from Poland, Hungary, and Italy lived in company towns and worked the coal fields. Inhumane conditions below ground and intense control at the hands of coal companies above ground, led to several attempts at unionizing over decades.

In some of these towns in West Virginia , while segregation was still the law of the land, communities subverted that. Children of different races went to school together, and one historian says, during attempts at unionization over the years, Black and white miners once held cafeteria workers at gunpoint until they were all served in the same room.

“We don’t want to exaggerate it and act like they were holding hands around the campfire, but at the same time they all understood that if they did not work together they couldn’t be effective,” Charles Keeney, author of The Road to Blair Mountain and descendant of a labor leader of this era, says. “The only way to shut down the mines was to make sure everybody participated.”5

Rather than succumb to racial divisions — like when the company brought more Black miners into the region with hopes to use them as strikebreakers — seeing common interests prevailed. By 1921, these miners decided to take arms to literally fight for their rights. On Blair Mountain, 10,000 white, immigrant, and Black coal miners waged a guerilla war in the forest for days against the coal industry that was supported by the National Guard and the US Army Air Force. It was the largest armed conflict on American soil since the Civil War. Black miners served in a wide range of union political positions. Black and white miners fought and led units side-by-side, and the concerns of all their families were woven into their struggle and demands. Together, they wore red bandanas around their necks as a makeshift rebel uniform — the real story behind the term “rednecks.”

“I call it a darn solid mass of different colors and tribes blended together, woven, bound, interlocked, tongued and grooved and glued together in one body.”

Fred Ball to United Mine Workers Journal, quoted by Joe William Trotter in Coal, Class and Color: Blacks in Southern West Virginia 1915-1932

Nuyorican Movement

A few months ago I attended a 20-year anniversary celebration of life event for the late, great Puerto Rican poet Pedro Pietri. He was a dear friend of my late aunt, ntozake shange. The commemorative event had living poets read the works of 20 late poets who were all connected to Pedro in some way. I was honored to have my aunt’s words read by her friend and fellow poet, Mariposa Hernandez.

Upon finishing her beautiful reading of zake’s excerpts, including “Bocas: A Daughter’s Geography” (one of my favorites), she had me come to the front…”Hey everyone, this is Alex, zake’s youngest niece with us here today. Zake was a part of our family – she had a passport, too.” All the Black and brown faces in front of me smiled, clapped. I smiled, probably did an awkward wave, and said thank you; I felt a bursting, contagious love.

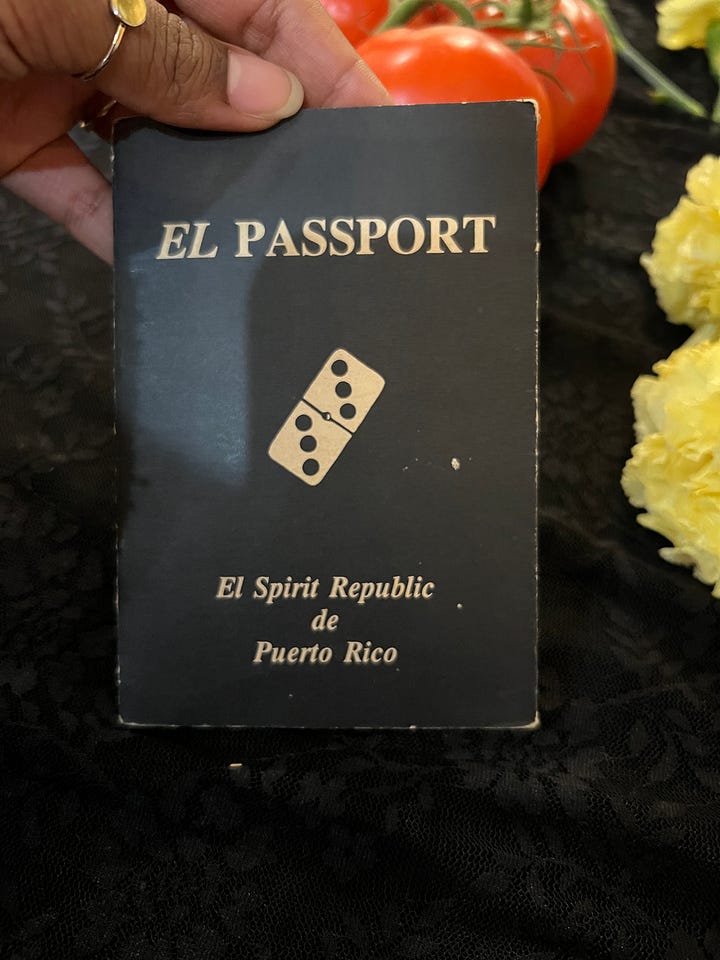

The passport Mariposa referred to was the “El Spirit Republic de Puerto Rico” passport — a literal passport Pedro made and bequeathed onto people who had the right to travel to “El Sovereign State of Mind of El Spirit Republic de Puerto Rico.”

When Mariposa says she had the passport, people in the audience knew it meant she belonged. The passport, and its creator Pedro, arose out of the Nuyorican movement, a tradition of poets, writers, artists, and musicians whose work spoke to the issues and spirit of Puerto Ricans in New York City in the 1960s and 1970s. Many of the writers were children of people who had migrated from Puerto Rico in the 1950s after the US conferred commonwealths status onto Puerto Rico or who had arrived in New York City as young children themselves.

As many people who spoke at this event described, the Nuyorican movement was inseparable from Black American artists and influence. It was a collective consciousness raising experience anchored in art and in the ability to see a shared humanity.

“Miguel Algarin, with the assistance of Miguel Pinero and Pedro Pietri, founded the Nuyorican Poets Cafe in 1973 on the Lower East Side, a community-run venue dedicated to the creation and showcasing of revolutionary art, music, and plays. The portmanteau, Nuyorican, which blended the Spanish term Nuyoricano, and the English phrase Puerto Rican, birthed a new identity for those who’d come of age in New York City, yet still connected to a colonized island. Unlike the term Boricua, Nuyorican carried a decidedly Gotham-based political consciousness, one where Blackness, island colonialism, poverty, and ghetto disenfranchisement in El Barrio were vividly expressed through the arts. Through proximity New York City’s harshest ghettos, and in artistic collaborations with Black American artists, Nuyoricans ushered in an era of Afro-Latino creative consciousness.”6

Puerto Rican poets in New York increasingly found themselves identifying with Black Americans as seen in the arts and in the political collaborations between the Black Panthers and the Young Lords. Out of this connectedness came such important art and a raising of a political consciousness that would go on (and continues to) shape the perspectives of generations of Americans.

“For many spoken word performers of color — especially those of Latinx and black descent — the Nuyorican Poets Cafe is what the Comedy Cellar has been for stand-up comics: a place to cut their teeth and test the resonance of their work in front of a live audience.” – “The Early Days of the Nuyorican Poets Cafe”, Concepción de León, The New York Times, 2018.

Rather than oppress each other (not to say it didn’t happen at all), we found each other through art, music, and a shared recognition of the joy of being alive.

So many small stories surfaced in that poetry reading and celebration of Pedro Pietri. So many warm embraces. So much love. I kept thinking about how could this love overflow into the streets and the parks and the schools and the buildings and the world outside of here?

Something about seeing our common struggle and our shared humanity can help us forge a new path. We can create a new trajectory, a new identity, a new sense of belonging when our imagination is expansive enough to see it.

So, what is the real story of the two men on Myrtle Avenue?

Spring has come since I first started writing this piece. Flowers are blooming and the air is warmer. As I strolled down Myrtle Avenue to Fort Greene yesterday, I saw him again. I recognized his smooth Black skin and chiseled jaw. We lock eyes. “Homeless veteran, can you spare any change, miss?”

This man most likely had people in his lineage who at one point came here through enslavement and migration. The other man, whom we call a migrant, arrived here most likely because of a desperation to live, to provide for himself and a family. For both of them, for most of us, America was not designed to be “ours.” But for centuries there have been examples of people who have been denied entry into one form of “we the people”, and have created alternative, beautiful ways to etch their belonging into the soil of this country.

Perhaps it is time to stop clawing on the walls of a place that was not designed for us, and instead create something that could be, collectively, ours.

Wilkerson is also the focus of the movie Origin and the author of the book Caste, which I recommend watching and reading. “Isabel Wilkerson: How did the Great Migration Change the Course of Human History?” (NPR, 2021)

Digital copy of referenced article (Visualizing the Red Summer)

“In 1919, a Mob in Maine Tarred and Feathered Two Black College Students” (Karen Seiber, Smithsonian Magazine, 2022)

The Elaine Massacre, Rosewood massacre, Tulsa race riots. I find PBS & Equal Justice Initiative’s archives as thoughtful re-tellers of histories we should all know.

“What Made the Battle of Blair Mountain the Largest Labor Uprising in American History” (Abby Lee Hood, Smithsonian Magazine, 2021)

“New York Black Arts Movement” (Shanna Collins, Voice of Young Dreamers, 2018)

Phenomenal piece. Please let’s work on getting it published somewhere.